Jesteś tutaj

Misinformation in New York Times article about Cord Blood Banking

On July 15, 2024 the NYT ran an article about family cord blood banking which was so negative that I find myself compelled to write this rebuttal. The NYT employs some of the world's best investigative journalists; I am a subscriber to the NYT and I read it every morning before I start my day. But the job of a journalist forces them to be a jack of all trades, master of none. In the course of their whirlwind investigation of cord blood banking, the authors of the NYT article got certain concepts confused and went for the cheap shot of spinning the story as a big scandal.

The NYT article showcased the personal experiences of four families that stored cord blood privately in the US, but then could not use the cord blood to treat their children because it was contaminated. Their stories are true, and each one is heart breaking for the families involved.

The biggest piece of misleading information in the NYT article is the statement that when clinical trials receive cord blood units from private banks, “more than half were rejected because of low-quality cells”. The phrasing of this statement may lead parents to believe that half of cord blood units stored in family banks are somehow tainted. In fact, when Dr. Kurtzberg’s team at Duke Medical Center first started studying cord blood therapy for neurologic conditions, they published that the contamination rate of privately banked units was 7.6%1. Dr. Kurtzberg has shared that more recently the contamination rate has been about 10%. These contaminated units cannot be used in the context of an FDA-approved clinical trial, even if the contamination is a simple microbe that could easily be countered with antibiotics. Bear in mind that birth is hardly a sterile process and family banks are relying on numerous obstetrics teams all over the country to perform collections. It would be helpful if obstetricians had more training in the best practices for cord blood collection.

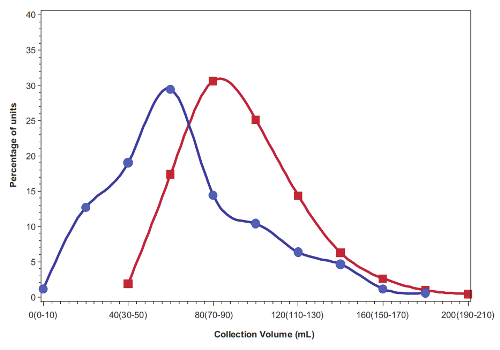

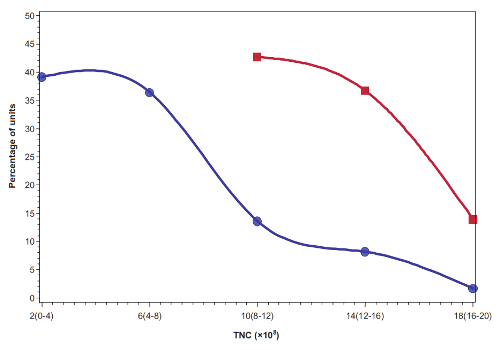

The primary reason that roughly half the cord blood units from family banks are rejected from clinical trials is because of their size. The current clinical trials being run by Dr. Kurtzberg’s team require that each child must receive a specific dose of stem cells per kg of weight, and many of the family cord blood collections are disqualified because they are not big enough to provide that dose. The median cord blood unit in US family banks has a volume of 60 mL (2 ounces) and contains 470 million total nucleated cells (TNC)1. By comparison, public cord blood banks can only afford to keep the biggest collections, the ones that have one to two billion TNC, and can be used to transplant an adult2. Hence public cord blood banks discard about 80% of the donations they receive2. Given this information, parents should not feel that something went wrong with their birth if they did not get a big cord blood collection, especially if there was delayed cord clamping before the collection. Parents need to be realistic about what is a normal collection size for the average baby.

The elephant in the middle of the room that was not discussed by the NYT article is that each of the disappointed parents they interviewed was trying to get their child into a clinical trial to treat cerebral palsy or autism. They were not trying to get a treatment for one of the 80+ diseases for which cord blood is a standard therapy and for which over 45,000 cord blood transplants have been performed worldwide3. So indirectly, the NYT article illustrates how cord blood has become a lifeline of hope for children with neurologic disorders, and how devastating it is when it is not available.

The NYT reported that “just 19 stem-cell transplants using a child’s own cord blood have been reported since 2010, according to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research” (CIBMTR). What the NYT authors did not explain is the CIBMTR only maintains records of cord blood transplants for the 80+ approved conditions, they do not track cord blood therapies in clinical trials and expanded access programs. The three largest cord blood banks in the US have published lists of their cord blood releases for therapies4-6. Collectively, by the end of 2023 they have enabled over 800 children to be treated with their own cord blood, and another 590 children provided cord blood treatment to a sibling4-6. Hence, while it remains a tragedy that a small number of families could not use their cord blood due to contamination, there have been over 1300 families that did use their privately stored cord blood.

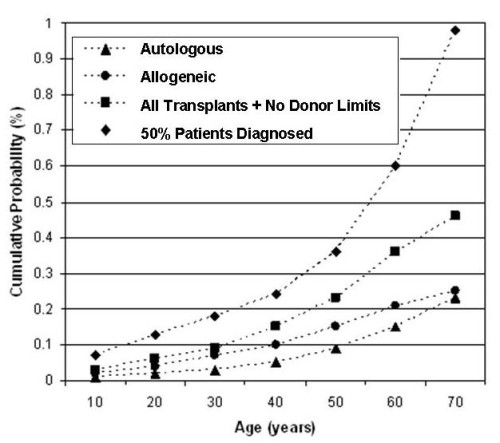

I was quoted by the NYT as saying that the marketing of cord blood to transplant 80+ diseases is “hype”. This quote requires some context. First, our website maintains a list of diseases treated that includes all diseases that can be cured by a stem cell transplant. Second, the choice of graft source for that stem cell transplant can be bone marrow, peripheral blood, or cord blood. The choice of graft source is made by the treating physician. It is not an exaggeration to say that cord blood could be used for any of these diseases. Third, the odds of a child having a stem cell transplant for any diagnosis before age 20 are only 3 in 5,000 in the US7. This is why I said that the chances of children using cord blood for any of the 80+ diseases are being hyped in marketing. But the odds of a child needing therapy with cord blood for conditions such as premature birth or cerebral palsy are much higher, and this is where I see the motivation for family banking.

I was quoted by the NYT as saying that the marketing of cord blood to transplant 80+ diseases is “hype”. This quote requires some context. First, our website maintains a list of diseases treated that includes all diseases that can be cured by a stem cell transplant. Second, the choice of graft source for that stem cell transplant can be bone marrow, peripheral blood, or cord blood. The choice of graft source is made by the treating physician. It is not an exaggeration to say that cord blood could be used for any of these diseases. Third, the odds of a child having a stem cell transplant for any diagnosis before age 20 are only 3 in 5,000 in the US7. This is why I said that the chances of children using cord blood for any of the 80+ diseases are being hyped in marketing. But the odds of a child needing therapy with cord blood for conditions such as premature birth or cerebral palsy are much higher, and this is where I see the motivation for family banking.

It is very important for parents to know that the list of diseases that are rare varies by country! The official definition of a rare disease is one that impacts less than 60 per 100,000 people in the population8. Within the US, the inherited blood disorders Sickle Cell Disease and Thalassemia are on the rare list. By contrast, Thalassemia is common throughout countries in the Middle East and Asia. For example, in India, there are 10,000 babies born each year with a severe variant of Thalassemia that requires a stem cell transplant for the child to survive9. Due to the prevalence of Thalassemia in their country, cord blood banking is more important as a form of biologic insurance for parents in India than it is for parents in the US.

Over the course of a 70-year lifetime, the likelihood of a person having a stem cell transplant rises to at least 1 in 2177. This statistic was published in a 2008 paper by Nietfeld et al., and I am one of the co-authors included in the “et al.” My friend J.J. Nietfeld, PhD, who has since retired, was the author that conceived of that study and led the effort to complete it, not Mary Horowitz, MD, as stated in the NYT article. We calculated the 1 in 217 odds of use based on the rate at which people were having stem cell transplants (having them, not just needing them) in the US during the years 2001-2003. The fraction of people having transplants might be notably higher now, given the increased access to transplantation over the past two decades, but the calculation has not been repeated.

The NYT article did expose some areas where family cord blood banks in the US could and should practice better quality control. The FDA requires that cord blood which is intended for transplant must undergo sterility testing to check for microbial or fungal contamination10. In public cord blood banks, any contaminated units are discarded. In family cord blood banks, because the biological samples are intended to be used in a family setting, the banks are allowed to save contaminated units. The two international agencies which accredit cord blood banks, AABB and FACT, both have protocols for how to handle and store contaminated units. When sterility testing turns up contamination, it is only fair and ethical that the parents who are paying to store the cord blood should be informed. Apparently family cord blood banks did not always do this in the past, according to the testimonials in the NYT article.

In conclusion, this rebuttal was necessary to make it clear that it is absolutely not true that roughly half the cord blood units in family banks are useless. I am the founder and director of the Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Foundation, a non-profit focused on parent education and patient advocacy. In writing this rebuttal I collaborated with the Cord Blood Association, a professional non-profit association for cord blood bankers. Together, we are issuing a call to action to the cord blood community: we call for family cord blood banks to routinely inform parents of the outcome of sterility testing on their child’s cord blood sample.

References

- Sun J, Allison J, McLaughlin C, Sledge L, Waters-Pick B, Wease S, Kurtzberg J. Differences in quality between privately and publicly banked umbilical cord blood units: a pilot study of autologous cord blood infusion in children with acquired neurologic disorders. Transfusion. 2010; 50(9):1980-1987.

- Ciubotariu R. Timing of Umbilical Cord Clamping and Impact on Cord Blood Volume Collected for Banking. Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Foundation Newsletter Published 2016-12

- Ballen K. Update on umbilical cord blood transplantation. F1000Res. 2017; 6:1556.

- How some CBR families have used newborn stem cells. (handout)

- Viacord Cord Blood in Action

- Cryo-Cell Transplant/Infusion Matrix

- Nietfeld JJ, Pasquini MC, Logan BR, Verter F, Horowitz MM. Lifetime probabilities of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the U.S. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008; 14(3):316-322.

- Crain E. What is a rare disease? Johnson & Johnson health & wellness blog. Published 2023-02-08

- Colah R, Italia K, Gorakshakar A. Burden of thalassemia in India: The road map for control. Pediatric Hematology Oncology 2017; 2(4):79-84.

- FDA Guidance for Industry. BLA for Minimally Manipulated, Unrelated Allogeneic Placental/Umbilical Cord Blood Intended for Hematopoietic and Immunologic Reconstitution in Patients with Disorders Affecting the Hematopoietic System. Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Published March 2014. (see sterility testing on page 16)