Jesteś tutaj

The Business Model of Community Banking in India

Traditional Business Model for Public Cord Blood Banks

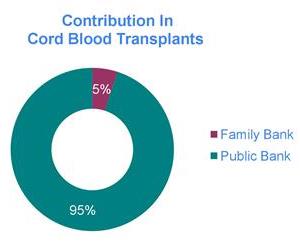

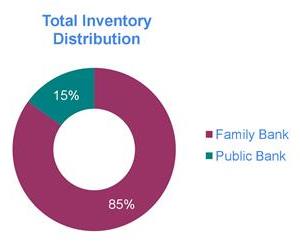

A paper was published in 2015 with the provocative title, “Banking or Bankrupting: Strategies for Sustaining the Economic Future of Public Cord Blood Banks”1. The authors included leading cord blood bankers and economists. The goal of this ground-breaking paper was to calculate a way for public cord blood banks to stay financially viable. Public cord blood banks fulfill the public health need for an inventory of donated cord blood that can save the lives of patients in need of a stem cell transplant.

For those who are not familiar with the field, here is a quick summary of the traditional business model of public cord blood banks: Public banks collect cord blood that is donated by the baby’s mother. The mother must undergo a detailed health history screening and give informed consent. Donation costs the mother nothing, but the family gives up all rights to the cord blood. The donated cord blood is screened for infectious diseases, contamination, tested to ensure that it holds a sufficient number of viable stem cells to transplant an adult, and then it is processed to concentrate stem cells that are finally cryogenically preserved.

Notice that all of the costs of testing and processing cord blood donations in a traditional public bank are borne by the bank. Adding to expenses, between 60% and 95% of donations are discarded, usually due to low volume but also due to problems with the consents2,3. Moreover, the cryopreserved units may sit in the bank inventory for years before being called as a match for a patient seeking a transplant. Hence this business model requires substantial upfront investment to launch and will not break even for years1. Costs are recovered when cryopreserved cord blood units (CBU) are sold for transplant, and in the United States the price of a transplant-grade CBU averages USD 36,2003.

It does not take a professional economist to see that the original business model of public cord blood banks is precarious. However, for a quarter of a century the network of public cord blood banks has been a vital public health resource for patients around the world seeking a donor to save them from life-threatening diseases requiring a stem cell transplant. During the first two decades of cord blood banking there were 35,000 cord blood transplants worldwide, saving patients who otherwise would not have a matching donor4.

Alternate Business Models For Public Cord Blood Banks

The viability of the public cord blood banking network is becoming increasingly precarious with each passing year. In the United States, about 25% of the active public banks have been acquired and/or have cut back their activities significantly within the past year5.

The viability of the public cord blood banking network is becoming increasingly precarious with each passing year. In the United States, about 25% of the active public banks have been acquired and/or have cut back their activities significantly within the past year5.

The paper titled “Banking or Bankrupting” concluded “Our study shows that the utilization rate of CBUs is paramount to the economic sustainability of public banks”. Once that paper explained the higher value of larger CBU, public banks have been pushing up the utilization rate of their inventory by only saving the largest donations; the high rate of discarded donations is an intentional business decision1. But this is not enough to stave off the falling demand for cord blood transplants in recent years. The World Marrow Donor Association reported that over the five year period 2013-2017 there was a 27% drop in the number of CBU shipped for transplant6.

Hopefully, new technologies that expand cord blood cells to speed their engraftment will help cord blood transplants to be more competitive against alternative transplant methods, and will also provide new applications for CBU as sources of NK cells, T-regs, etc.7

For about a decade now, alternatives have been proposed that link public and private cord blood banks to each other in business models called “Hybrid” banking or “Crossover” banking. These names have not been applied consistently, but the underlying ideas are simple to describe.

In hybrid banking, a public and a private cord blood bank operate under the same management, and profits from the private bank help to support the public bank. Other than the profit sharing, the two banks often operate independently, and may have separate laboratories. The world’s largest example of successful hybrid banking is the nation China, where only one cord blood bank is licensed by the government in each province, and that bank is required to follow the hybrid model8. However, in other countries the hybrid model has not been the salvation of public banks. In most free markets there is intense competition between family cord blood banks on price and market share. In order to survive, family banks must allocate a significant portion of their profit margin towards marketing. As a result, a hybrid bank that competes against family banks is pressured to focus most of their resources on promoting their family banking at the expense, literally, of their public banking activities.

In hybrid banking, a public and a private cord blood bank operate under the same management, and profits from the private bank help to support the public bank. Other than the profit sharing, the two banks often operate independently, and may have separate laboratories. The world’s largest example of successful hybrid banking is the nation China, where only one cord blood bank is licensed by the government in each province, and that bank is required to follow the hybrid model8. However, in other countries the hybrid model has not been the salvation of public banks. In most free markets there is intense competition between family cord blood banks on price and market share. In order to survive, family banks must allocate a significant portion of their profit margin towards marketing. As a result, a hybrid bank that competes against family banks is pressured to focus most of their resources on promoting their family banking at the expense, literally, of their public banking activities.

Crossover banking is a more intertwined mixture of family and public banking. In this business model, parents pay to store their child’s CBU privately, but they also agree to give up their child’s CBU if it is a match for any patient in need. In the event that parents must give up the CBU, they will be reimbursed for their expenses. In Spain, crossover banking is mandated for any family banks that store within the country9.

Crossover banking requires that every CBU must be banked to the quality standards of public banks and HLA typed, because every CBU may potentially be used for an unrelated donor. This imposes higher operating costs on crossover banks, which makes it challenging for them to compete against strictly private banks on consumer price. Internationally, only a handful of family banks offer this option, and typically those parents that opt into the crossover program pay extra to participate.

How Community or Pool Banking Works

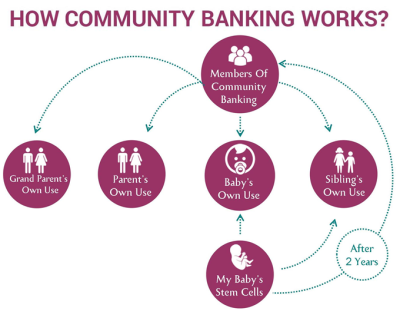

In this model, a community of parents agrees to share their children’s cord blood with each other. The community pool is like a private bank, in that only members can participate, but it is also a public bank, because all the members agree to donate their CBU if another member needs it. This type of bank is affordable to launch because when members join the pool they pay a fee that covers the costs of having their child’s CBU processed and tested. The community banking model is as new as the sharing economy that brought us Airbnb and Uber, and as old as the mutual aid societies that evolved to become today’s insurance companies.

In this model, a community of parents agrees to share their children’s cord blood with each other. The community pool is like a private bank, in that only members can participate, but it is also a public bank, because all the members agree to donate their CBU if another member needs it. This type of bank is affordable to launch because when members join the pool they pay a fee that covers the costs of having their child’s CBU processed and tested. The community banking model is as new as the sharing economy that brought us Airbnb and Uber, and as old as the mutual aid societies that evolved to become today’s insurance companies.

A survey which demonstrates that parents and expectant parents support intertwined public and private banking models was taken in Switzerland10. The overwhelming majority of participants, 92%, supported cord blood donation, and given the choice they favored banking in a crossover model over strictly private banking by 47% to 13%10. (Please note this survey used the word “hybrid” for what we call “crossover”). Moreover, the majority of survey participants, 84% overall, had no problem with the fact that all clients in a crossover bank must answer the health eligibility questions and qualify for public donation10.

Community or pool banking is not a pure public health resource, because donors and their families only support the transplant needs of other participants; the donations are not available to any patient in the greater public society. However we will explain below that community banking can fulfill unmet public health needs for some populations that lack alternatives. Moreover, the community bank also functions as a health insurance policy. This model of community or pool banking is significantly different from the traditional models of both public and private cord blood banking.

Application of Community or Pool Banking to India

India has a desperate need for innovative ways to provide stem cell transplants. India has a large and genetically diverse population11, but India has very limited registries of adult donors or banks of donated CBU12.

The latest United Nations census data counts the population of India as 1.37 billion, about 17% of the world total13. In all nations, stem cell transplants are used to treat severe cases of blood and immune disorders. India has approximately 100,000 patients diagnosed annually with leukemia and lymphoma14. In addition, India has a high burden of the inherited blood disease thalassemia15, which in severe cases is best treated by stem cell transplant16. There are approximately 35-45 million carriers of the beta-thalassemia variant in India, where the mean prevalence is 3-4% of the population, although the prevalence runs higher in some ethnic groups15. As a result, there are about 100,000 patients suffering from thalassemia major in India, and this number keeps growing as 10,000 afflicted babies are born each year15.

The lack of matching stem cell donors for Indian patients is a well-documented problem. A detailed study of HLA match likelihoods for Indian patients was conducted by biostatisticians from NMDP in the United States and leading doctors in India12. They found that even if the Indian adult registry grew to 1 million donors, due to the genetic diversity of Indians, only 60.6% of patients could obtain bone marrow transplants with the desired 10/10 HLA match12. But the matching flexibility of cord blood can solve the donor shortage; an inventory of only 25,000 CBU from Indian births would provide adequate 4/6 matched cord blood transplants for 96.4% of patients12.

Economic Viability of Community or Pool Banking in India

The big question about community banking remains: Will the bank be sustainable as members start withdrawing cord blood units for therapy? To answer that, we have to look at the disease burden in a different way: not in terms of how many people may be diagnosed with a transplantable illness, but how many people will actually get transplants, and how much does each transplant cost the community bank? In India, the median cost of the hospital stay for a bone marrow stem cell transplant from an unrelated donor is near INR 12.5 lakh18. (Units: INR are Indian National Rupees and the word “lakh” means 100,000).

The big question about community banking remains: Will the bank be sustainable as members start withdrawing cord blood units for therapy? To answer that, we have to look at the disease burden in a different way: not in terms of how many people may be diagnosed with a transplantable illness, but how many people will actually get transplants, and how much does each transplant cost the community bank? In India, the median cost of the hospital stay for a bone marrow stem cell transplant from an unrelated donor is near INR 12.5 lakh18. (Units: INR are Indian National Rupees and the word “lakh” means 100,000).

To learn how much transplants cost the Community Bank, we look at the financial model of LifeCell International. Each CBU in the community pool was contributed by a child that probably has 9 family members, based on the latest UN census of India: the child itself, 2 siblings, 2 parents, and 4 grandparents13. All 9 of these family members are eligible to withdraw CBUs from the pool for transplant, an unlimited number of times, absolutely free of cost, for 75 years after the date of joining17. If a member does withdraw a CBU from the community bank, the family that donated that CBU will be reimbursed for their banking expenses – but they can continue to participate until their child reaches age 75 years. In addition, when a first degree relative of a donor receives a stem cell transplant, no matter where they find the matching stem cells or where they receive the transplant, the bank will pay out INR 20 lakhs towards their medical expenses, for every hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, for the initial 21 years after the date of joining17. This aspect of the LifeCell Community Bank is a stem cell transplant insurance policy that covers the child, the child’s biological siblings, and the child’s biological parents, which is typically 5 family members13. Hence, the bank is responsible to pay out INR 20 lakhs per transplant in a population that is 5 times larger than the number of donors.

In the year 2016, the United States had 8830 allogeneic stem cell transplants in a population of 323 million19. That same year, India had 1878 transplants in a population of 1.324 billion – 19 times less than the US rate20. Right now only 0.00014% of Indians receive a stem cell transplant each year, so based on that national average, the 50,000 families of 5 eligible members that participate in the LIfeCell community bank will only generate 0.36 transplants per year. The clients of cord blood banks tend to belong to the more wealthy classes in India, and can travel abroad for medical care, which increases the likelihood that they will have transplants. But even if the transplant rate were as high as the rate in the US, the community bank would only have to cover a handful of withdrawals per year.

For a community or pool bank, the financial bottom line is a comparison of bank income from storage fees versus bank payments to cover transplants. For example, LifeCell International charges annual storage fees of INR 4000 per client. Because they currently have 50,000 families participating in their pool, this amounts to INR 2,000 lakhs (INR 20 crores) in annual income. This income is enough to pay out INR 20 lakhs for up to 100 transplants per year. Therefore, the community banking model is very economically viable as a stand-alone transplant insurance program for Indians. Even as the number of stem cell transplants in India rises, due to improving hospital infrastructure and more efforts to transplant patients with leukemia, thalassemia, etc., the community bank should still be able to support the need for matching CBUs and the rising cost of withdrawals. The LifeCell Community Bank is also viable as a business that competes against family (private) banks, because the first year fee to join their community bank is less than the first year fee of competing family banks in India21.

Application of Community or Pool Banking to other countries

In most western countries, stem cell transplants from unrelated donors are very strictly regulated, so that operating the laboratory of a community bank to public banking standards would be very expensive22. These operating costs would make it difficult for a community bank to compete against family banks on price. Nonetheless, any community that is under-represented by matching donors, or under-served by the ability of their public banking network to build inventory, might find the community banking model desirable.

We may yet see greater adoption of community or pool banking. As proof that there is industry interest in this model, FamiCord Group, the largest cord blood bank in Europe, signed a letter of intent in April 2019 to acquire the Indian bank MyCord or CelluGen Biotech that advertises “pool banking”23.

Key Take Aways

|

References

- Magalon J, Maiers M, Kurtzberg J, Navarrete C, Rubinstein P, Brown C, Schramm C, Larghero J, Katsahian S, Chabannon C, Picard C, Platz A, Schmidt A, Katz G. Banking or Bankrupting: Strategies for Sustaining the Economic Future of Public Cord Blood Banks. 2015; PLOS https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143440

- Verter F. RAND Corporation report on Public Cord Blood Banking Industry. Nov. 2017; Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Newsletter

- Kapinos KA, Briscombe B, Gračner T, Strong A, Whaley C, Hoch E, Hlávka JP, Case SR, Chen PG. Challenges to the Sustainability of the U.S. Public Cord Blood System. 2017; RAND Corporation https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1898

- Ballen KK, Verter F, Kurtzberg J. Umbilical cord blood donation: public or private? 2015; Nature Bone Marrow Transpl 50:1271–1278

- Verter F. private communication re Public Cord Blood Banking in United States

- World Marrow Donor Association 2017 annual report Accessed from https://www.wmda.info/

- Verter F, Bersenev A., Silva Couto P. Clinical Trials of Expanded Cord Blood. May 2018; Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Newsletter

- Chang H-C. The role of policies and networks in development of cord blood usage in China. 2017; Regenerative Medicine 12(6):637-645

- Sánchez Córcoles A. Cord Blood Banking in Spain: Public, Private, and Cross-Over from Private to Public April 2015; Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Newsletter

- Wagner A-M, Krenger W, Suter E, Ben Hassem D, Surbek DV. High acceptance rate of hybrid allogeneic–autologous umbilical cord blood banking among actual and potential Swiss donors. 2013; Transfusion 53(7):1510-1519

- Indian Genome Variation Consortium. Genetic landscape of the people of India: a canvas for disease gene exploration. 2008; Journal of Genetics 87(1):3-20.

- Maiers M, Halagan M, Joshi S, Ballal HS, Jagannatthan L, Damodar S, Srinivasan P, Narayan S, Khattry N, Malhotra P, Minz RW, Shah SA, Rajagopal R, Cereb N, Yang SY, Parekh S, Mammen J, Daniels D, Weisdorf D. HLA match likelihoods for Indian patients seeking unrelated donor transplantation grafts: a population-based study. 2014; Lancet Haematology 1(2):e57-63

- UN Census 2019 data; sourced from: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/india-population/

- Takiar R, Nadayil D, Nandakumar A. Projections of number of cancer cases in India (2010-2020) by cancer groups. 2010; Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 11:1045-1049

- Colah R, Italia K, Gorakshakar A. Burden of thalassemia in India: The road map for control. 2017; Pediatric Hematology Oncology 2(4):79-84

- John MJ, Jyani G, Jindal A, Mashon RS, Mathew A, Kakkar S, Bahuguna P, Prinja S. Cost Effectiveness of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Compared with Transfusion Chelation for Treatment of Thalassemia Major. 2018; Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 24(10):2119-2126

- Mandot V. LifeCell’s Community Cord Blood Banking Aligns With Recommendations of India’s Medical Bodies. July 2018; Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Newsletter

- Sharma SJ, Choudhary D, Gupta N, Dhamija M, Khandelwal V, Kharya G, Handoo A, Setia R, Arora A. Cost of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in India. 2014; Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2014; 6(1): e2014046

- United States Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). 2016; How many bone marrow or umbilical cord blood transplants are performed in the United States?

- Naithani, R. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in India-2017 Annual Update. 2018; Indian J Hem Blood Transf 34(1):5-7.

- Parent’s Guide to Cord Blood Foundation web page of Family cord blood banking in India

- Rao MS. Cord Blood and the FDA. Jan. 2015; Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Newsletter

- Business Standard. 25 April 2019; Europe's biggest cord blood bank FamiCord Group signs letter of intent with Indian CelluGen Group

Community or Pool Banking Supports Public Banking Without Bankrupting.

Community or Pool Banking Supports Public Banking Without Bankrupting. Community or pool banking is an alternative to both the public and private banking models.

Community or pool banking is an alternative to both the public and private banking models.