Jesteś tutaj

Stem Cell Therapies for AutoImmune Diseases such as Multiple Sclerosis

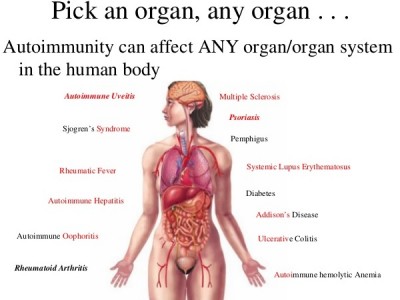

For decades, physicians have relied on stem cell transplants to reset the immune system of patients who have hematologic cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma. This has led researchers to wonder if stem cell transplants could also reset the immune system so that it would not attack the patient’s own body in autoimmune diseases, such as Multiple Sclerosis, Lupus, and Rheumatoid Arthritis. There are more than 80 types of autoimmune diseases.

For decades, physicians have relied on stem cell transplants to reset the immune system of patients who have hematologic cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma. This has led researchers to wonder if stem cell transplants could also reset the immune system so that it would not attack the patient’s own body in autoimmune diseases, such as Multiple Sclerosis, Lupus, and Rheumatoid Arthritis. There are more than 80 types of autoimmune diseases.

To date, most stem cell therapies for auto-immune diseases have been transplants of the patient’s own (autologous) stem cells. This type of therapy could be accessible to many patients if it is proven effective, since there is no need to search for a matching stem cell donor. Today’s adult patients are undergoing autologous transplants with stem cells harvested from their bone marrow or peripheral blood, but today’s children could use their own cord blood for autologous transplants if they develop an autoimmune disease later in life. Another advantage of patients using their own stem cells is that the transplant requires less severe chemotherapy conditioning, which decreases the risk of complications such as life-threatening infections.

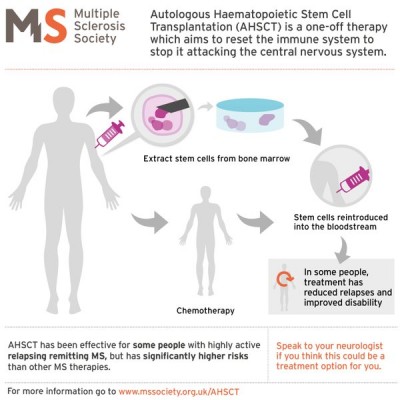

Some very exciting results have been reported within the past year from clinical trials of stem cell transplants for Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Very briefly, in MS the patient’s immune system attacks myelin, the fatty protective sheath around nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord, causing inflammation and creating lesions that are visible in magnetic resonance images (MRI). For more information please see the embedded video from the National MS Society or visit their website: nationalmssociety.org

Like other autoimmune conditions, MS is more common among women than men. The number of patients living with MS is estimated to be 2.5 million worldwide, including 400,000 in the USA and 100,000 in the UK. (See: Who Gets MS?, and Autoimmunity Is From Venus)

At Northwestern University in Chicago, a group led by Dr. Richard Burt has given autologous stem cell transplants as experimental treatment for about 23 different autoimmune diseases. Although the group has avoided publicity, some of their patients have reported remarkable recoveries, and the group has published many scholarly articles about their work.

In 2015 Dr. Burt’s group published a retrospective study of outcomes for 151 MS patients who had received autologous stem cell transplants and were followed for two to four years post-transplant. The patients showed statistically significant improvements by many measures: Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score, Neurologic Rating Scale (NRS), Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC), quality of life, and lesion volume. Perhaps the most compelling statistic is that progression-free survival was 87% for patients at the four year mark. This is important, because MS sometimes stops and starts again of its own accord, so attaining a sustained remission suggests that the stem cell transplant has been beneficial.

When a physician described the outcomes as "miraculous", a clinical trial of stem cell transplants for MS at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield UK received huge media coverage. Two of the patients interviewed for a story in the Daily Mail newspaper were wheelchair bound going into the trial, but emerged with the ability to walk. Unfortunately, not every MS patient who has a stem cell transplant experiences "profound neurological improvements".

The MS Society of the UK has prepared a tutorial (see the accompanying graphic) for patients who are considering autologous stem cell transplants. They caution that MS patients should weigh the potential benefits of stem cell transplants against the risks, especially as compared to other MS treatment options. Studies are still underway to determine which MS patients are the best candidates for stem cell transplants.

The MS Society of the UK has prepared a tutorial (see the accompanying graphic) for patients who are considering autologous stem cell transplants. They caution that MS patients should weigh the potential benefits of stem cell transplants against the risks, especially as compared to other MS treatment options. Studies are still underway to determine which MS patients are the best candidates for stem cell transplants.

Meanwhile, a variety of new stem cell therapies are emerging for MS and other autoimmune diseases that are not traditional “stem cell transplants”. To review, in a traditional transplant, patients initially receive chemotherapy to suppress or wipe out their native immune system. Second, a transplant gives the patient blood-forming stem cells (hematopoietic stem cells, or HSC) to build a new immune system. Third, in a transplant the stem cells are delivered by infusion into a major blood vessel.

Today, the majority of patients in clinical trials that use cell therapy to treat autoimmune diseases receive infusions of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC).

The accompanying article illustrates the statistics on clinical trials from the past five years. Many of these clinical trials are relying on stem cells to modulate the patient’s immune system, but not to completely replace it. A worldwide review article published by Chen & Ding in Feb. 2016 identified 16 trials using MSC cell therapy for MS patients, conducted in 11 countries and using a variety of graft sources: MSC from bone marrow, from umbilical cord tissue, and from adipose tissue. Our accompanying article finds that among 58 clinical trials for any autoimmune disease that were registered over the past five years, 62% of patients are receiving MSC therapy.

One new approach to treating MS patients using MSC is a phase 1 clinical trial at the Tisch MS Research Center in New York (NCT01933802). The trial, led by center director Dr. Saud A Sadiq, uses autologous MSC from the patient’s bone marrow which they manipulate in the laboratory to derive “neural progenitor” stem cells (pre-clinical publication). In this Tisch trial the patients do not receive chemotherapy, and the cord blood stem cells are administered via three intrathecal injections (injections into the cerebrospinal fluid) of 2-10 million cells per dose at 3 month intervals. Although this Tisch trial was only intended to assess the safety of the intrathecal method of stem cell delivery, they report that 70% of 10 MS patients treated so far had improvement in their level of disability (publication).

The transition to treating autoimmune diseases with MSC instead of HSC leads to many new options for patients. On the one hand, today’s children could use MSC from their own cord tissue or placenta for personalized stem cell therapy of any autoimmune disease they may develop later in life. On the other hand, banks of donated perinatal stem cells could become sources for off-the-shelf stem cell therapies in which patients do not have to provide their own stem cells. The accompanying story of Hepsi Zsoldos tells how donated cord blood helped one patient with an autoimmune disease.

The future of stem cell therapy for autoimmune diseases such as MS shows great hope. If anything, patients now face a bewildering variety of clinical trial choices, in terms of what stem cells the trials are using, how the patients are prepared, and how the cells are delivered. Hopefully the next decade of research will bring some clarity to the competing efforts to stop and ultimately cure MS.