Usted está aquí

Cord Blood plus Erythropoietin is Better for Cerebral Palsy than Either Alone

The latest study of cord blood therapy for Cerebral Palsy was published in November 20201. This was the most elaborate study to date of cell therapy for cerebral palsy: patients were assigned randomly to one of 4 treatment arms, and careful procedures were used to keep the doctors and patients “blind” as to who was in which group. The study was first registered as a clinical trial in 2013 and eventually treated 88 patients.

This study was led by MinYoung Kim, MD PhD, of the CHA Bundang Medical Center near Seoul, South Korea. Their group has built a protocol for treating cerebral palsy that is based on intravenous infusions of donated cord blood from a public bank. The cord blood is matched to the patient on at least 4 of 6 key HLA types, and they may use up to two cord blood units to achieve their target dose of at least 30 million cells per kg of patient weight. Dr. Kim’s group has been publishing results of their approach since 20131-3.

Parents in the United States are more familiar with the treatment protocol developed by Joanne Kurtzberg, MD, at Duke University. The Duke protocol is also based on intravenous infusions of cord blood. The key difference is that Duke originally treated children with their own cord blood, starting in 2005 and finally publishing their first paper in 20174. Since then, Duke has received FDA permission to run an expanded access program giving sibling cord blood to children with cerebral palsy. The first Duke clinical trial using donated cord blood for cerebral palsy, called ACCeNT-CP, began in 2018 and recently completed, with preliminary results to be announced in early 2021.

Aside from the emphasis on personal (autologous) cord blood in the United States versus donated cord blood in South Korea, another key difference between these two groups is the use of Erythropoietin as part of cord blood therapy for cerebral palsy. Erythropoietin, nicknamed EPO, is a natural human hormone that stimulates the bone marrow to produce more red blood cells. Pharmaceutical companies have been manufacturing EPO for decades. Artificial EPO is routinely used during kidney dialysis, during cancer therapy, and has been implicated as a performance enhancing drug in athletics scandals5.

The cerebral palsy cell therapy protocol developed by Dr. MinYoung Kim’s group gives an injection of EPO just before the umbilical cord blood (UCB) infusion, and five follow up injections of EPO at three-day intervals. Their philosophy of treatment is that the EPO “potentiates” the cell therapy, because EPO has neuro-protective and neural-repair properties, particularly in the setting of brain injury at birth (the medical references for this can be found in their first paper)2.

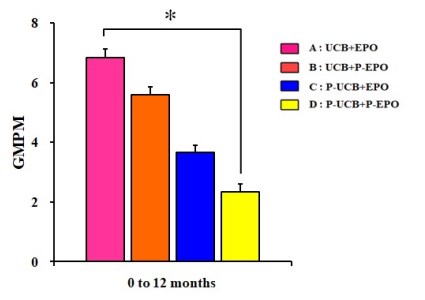

Initially, Dr. MinYoung Kim’s group ran a study that had 3-arms: UCB+EPO (31 patients), EPO alone (33), and a control group (32)2. That study, published in 2013, showed a clear benefit for UCB+EPO versus the other two arms when patient skills were measured with the GMPM scale of “gross motor performance measure”. However, when patient skills were tested on the GMFM scale of “gross motor functional measure”, the results for UCB+EPO were not distinguishable from EPO alone, although both were better than the control. Consequently, some researchers have been skeptical whether the UCB or the EPO was the more important component of the therapy. This is particularly true in the west, where the GMFM scale is more universally adopted than GMPM6. This story also illustrates how tricky it is to measure the outcome of a cerebral palsy intervention: partly because all children improve over time so the intervention must have better improvement than the control, and partly because there are multiple ways to measure improvement.

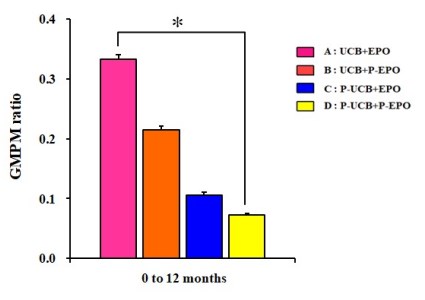

Almost eight years after the release of their first study, Dr. MinYoung Kim’s group has now published a study with 4-arms: UCB+EPO (22 patients), UCB alone (24), EPO alone (20), and a control group (22)1. This latest study explored multiple different ways of measuring outcome (including several types of brain imaging), plus different ways of stratifying the patients, and the full results are beyond what we can summarize here. The paper is published open access and comes with 18 supplemental files of data that can be downloaded. Overall, the results for motor skills confirm their original study: UCB+EPO clearly shows the best improvement when measured on the GMPM scale. Their improvements on the GMFM scale were not statistically significant. When using GMPM ratios to eliminate baseline variations, UCB+EPO is 50% better than UCB alone, and three times better than EPO alone or control.

Almost eight years after the release of their first study, Dr. MinYoung Kim’s group has now published a study with 4-arms: UCB+EPO (22 patients), UCB alone (24), EPO alone (20), and a control group (22)1. This latest study explored multiple different ways of measuring outcome (including several types of brain imaging), plus different ways of stratifying the patients, and the full results are beyond what we can summarize here. The paper is published open access and comes with 18 supplemental files of data that can be downloaded. Overall, the results for motor skills confirm their original study: UCB+EPO clearly shows the best improvement when measured on the GMPM scale. Their improvements on the GMFM scale were not statistically significant. When using GMPM ratios to eliminate baseline variations, UCB+EPO is 50% better than UCB alone, and three times better than EPO alone or control.

To be realistic, when parents of children with cerebral palsy seek a cell therapy intervention, the biggest challenge they face is finding a study or a clinic where they can access treatment8. There are only a few well-established treatment centers around the world that offer cell therapy for cerebral palsy, and thus parent treatment decisions are usually driven by travel distance and cost. The CHA Bundang Medical Center does offer their cerebral palsy therapy to visiting stem cell tourists9. Appointments can be made with an on-line form or via email to intnl@chamc.co.kr.

Secondary take-aways for parents to keep in mind are that the top research groups led by Dr. MinYoung Kim and by Dr. Joanne Kurtzberg are in agreement about the major trends in cord blood therapy for cerebral palsy: younger children tend to respond better, bigger cell doses are better, and cord blood that is a closer HLA match to the patient is better (the closest match is their own cord blood). The agreements between these two groups are more important than the differences in their protocols.

References

- Min K, Suh MR, Cho KH, Park W, Kang MS, Jang SJ, Kim SH, Rhie S, Choi JI, Kim HJ, Cha KY, & Kim MY. Potentiation of cord blood cell therapy with erythropoietin for children with CP: a 2×2 factorial randomized placebo-controlled trial. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2020; 11:509

- Min K, Song J, Kang JY, Ko J, Ryu JS, Kang MS, Jang SJ, Kim SH, Oh D, Kim MK, Kim SS & Kim M. Umbilical Cord Blood Therapy Potentiated with Erythropoietin for Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Double-blind, Randomized, Placebo Controlled Trial. Stem Cells 2013; 31(3):581-591.

- Kang M, Min K, Jang J, Kim SC, Kang MS, Jang SJ, Lee JY, Kim SH, Kim MK, An SSA, & Kim, M. Involvement of Immune Responses in the Efficacy of Cord Blood Cell Therapy for Cerebral Palsy. Stem cells and development 2015; 24(19):2259-2268.

- Sun JM, Song AW, Case LE, Mikati MA, Gustafson KE, Simmons R, Goldstein R, Petry J, McLaughlin C, Waters‐Pick B, Chen LW, Wease S, Blackwell B, Worley G, Troy J, & Kurtzberg J. Effect of Autologous Cord Blood Infusion on Motor Function and Brain Connectivity in Young Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized, Placebo‐Controlled Trial. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 2017; 6(12):2071-2078

- Maiese K, Li F, & Chong ZZ. New Avenues of Exploration for Erythropoietin. JAMA 2005; 293(1):90-95.

- Ko J & Kim M. Inter-rater Reliability of the K-GMFM-88 and the GMPM for Children with Cerebral Palsy. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012; 36(2):233–239.

- Verter F. Cerebral Palsy Cell Therapy Comparison. Parent’s Guide to Cord Blood Foundation. Newsletter Published April.2018 - FREE DATA DOWNLOAD

- Paton M. Cerebral Palsy Alliance Stem Cell Tourism Survey. Parent’s Guide to Cord Blood Foundation. Newsletter Published Nov.2019

- Verter F. First US patient treated in South Korea for Cerebral Palsy. Parent’s Guide to Cord Blood Foundation. Newsletter Published Dec.2014