Usted está aquí

Cord Blood and the FDA

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or USFDA) is a federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA was first formed in 1906, but in 1938 then President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed a new Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) which greatly increased the power of the FDA. Soon after 1938, the FDA began to designate certain drugs as safe for use only under the supervision of a medical professional, and this category of "prescription-only" drugs was securely codified into law by the 1951 Durham-Humphrey Amendment.

A revolution in FDA regulatory authority came about in 1962 when the Kefauver-Harris Amendment to the FD&C Act was passed. The most important change was the requirement that all new drug applications demonstrate "substantial evidence" of the drug's efficacy for a marketed indication, in addition to the existing requirement for pre-marketing demonstration of safety. This marked the start of the FDA approval process in its modern form.

The FDA now plays a critical role in ensuring the safety and quality of all food, cosmetics, OTC drugs, medical devices, small molecule drugs, biologics and live animal products for medicinal purposes in the United States.

Congress was careful to limit the authority of the FDA to ensuring safety and efficacy of products, while distinguishing that authority from the "practice of medicine". The practice of medicine has traditionally remained in the domain of medical authorities such as physicians and surgeons. Thus, the FDA can tell a doctor which drugs have been proven safe and effective for certain indications, but cannot tell doctors how to use them or where not to use them. This allows doctors to use their discretion to prescribe drugs for "off label" indications, where the FDA has not tested the efficacy of the drug.

The regulatory pathway for FDA approval of a new medical product differs depending on how the product is designated. The manufacturer of the product will apply for FDA licensing either under an IND (initial new drug application) or an IDE (investigational device exemption) or a BLA (biological licensure application). Each of these regulatory pathways requires that the drug or device prove its efficacy in clinical trials, a process that can take years.

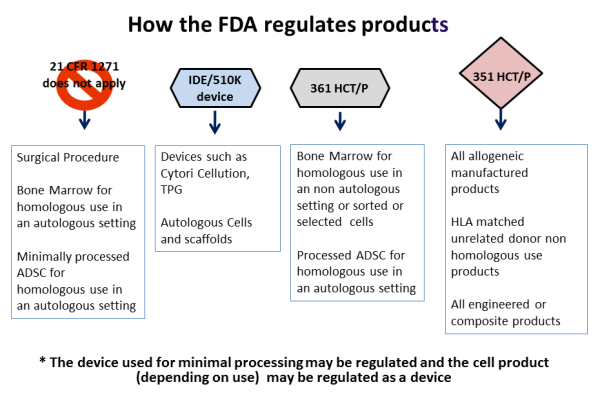

With respect to stem cells from bone marrow or cord blood, prior to 2010 the FDA regarded stem cell transplants as a surgical procedure. Under this regulatory status, the steps involved in processing the stem cells for transplant were considered to be "minimal manipulation", akin to how a surgeon might harvest and manipulate skin or blood vessels for transplant. The status of "minimal manipulation" meant that the transplanted stem cells were not an FDA regulated product, although the FDA still had safety oversight under the Human Tissue and Cell Procurement Act.

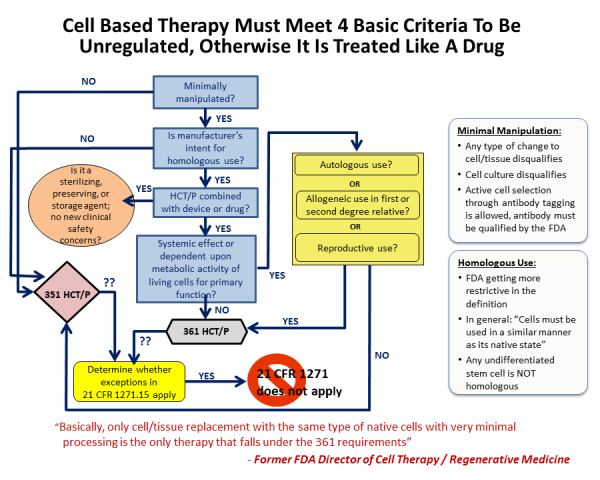

The FDA commissioner outlined four guiding principles to distinguish between a minimally manipulated product versus a drug product, for hematopoietic cell therapy products (called HCT/P in FDA parlance), in a 2009 publication.

Principle one: The process of obtaining the tissue or cells had to be "minimal", although the FDA did not fully define this term.

Principle two: The basic qualities and character of the cells or tissue remained unchanged throughout the steps of harvesting, processing, and transplant.

Principle three: The use of the cells has to be "homologous". Homologous is a biology term used to describe structures that have a shared ancestry, whether or not they currently serve a similar function. As defined by the FDA, "Homologous use means the repair, reconstruction, replacement, or supplementation of a recipient's cells or tissues with an HCT/P that performs the same basic function or functions in the recipient as in the donor."

In effect principle three means native use: the cells should do what they normally do. This may be straightforward for red blood cells, but is not as clear for some stem cells where we don't know all of the things they do or even where they are located. The ruling means that giving blood-forming stem cells from bone marrow or cord blood for the treatment of blood disorders qualifies as homologous use, but using CD34+ cells from cord blood to treat stroke does not. However if a researcher could demonstrate that cord blood CD34+ cells already have the capability to treat stroke in vivo, then this would be reclassified as homologous use.

Principle four: Minimally manipulated cells should not be combined with another product. So injecting bone cells into bone is not regulated, but if you first place those cells into a bone scaffold and then transplant them, they would be regulated as a drug product.

To review some examples of these four principles in action: Stem cell therapies derived from bone marrow or cord blood require FDA regulation when the cells are sorted (changes to their character), the cells are grown in culture (more than minimal manipulation), the cells are used to treat a part of the body other than the immune system (for example cord blood therapy for brain injury is non-homologous use), or if the cells undergo gene engineering or are seeded into a scaffold (combined with other materials). Under all these circumstances the FDA regulates stem cells as a prescription drug, and requires the "manufacturer" to obtain an FDA Biologics License.

Cord blood banks are impacted by these FDA clarifications as follows: Therapy with blood-forming stem cells from cord blood is considered practice of medicine and not FDA regulated so long as the stem cells are only used with minimal manipulation to reconstitute the donor's immune system. However if they are used for other purposes or given to unrelated patients then they are considered a drug product.

These FDA rulings raise a lot of questions for cord blood banks: Do the normal operations undertaken by a cord blood bank to harvest, isolate, and cryopreserve cord blood stem cells constitute more than minimal manipulation? So far the answer has been no, because these steps do not sufficiently change the character of the cells; but this answer is an opinion and not law.

The current FDA guidelines create a sharp distinction between public cord blood banks versus family banks. Family cord blood banks have been given the green light to treat relatives of the donor without FDA licensing, whereas public cord blood banks that treat unrelated patients are required to apply for Biologics Licensing.

The guidance that requires public cord blood banks to submit a Biologics License Application was proposed in 2007, and became effective 2009. Over the following decade eight of the U.S. public cord blood banks have completed the rigorous BLA requirements:

- National Cord Blood Program at NY Blood Center

(Nov. 2011 product HEMACORDTM) - ClinImmune Labs at the University of Colorado

(May 2012 product HPC, Cord Blood) - Carolinas Cord Blood Bank at Duke University Medical Center

(Oct. 2012 product DUCORDTM) - St. Louis Cord Blood Bank at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children's Medical Center

(June 2013 product ALLOCORD) - LifeCord Cord Blood Bank at LifeSouth Community Blood Centers

(June 2013 product HPC, Cord Blood) - BloodworksNW (laboratory for EvercordTM family bank)

(Jan. 2016 product HPC, Cord Blood) - Cleveland Cord Blood Center

(Sept. 2016 product CLEVECORDTM) - M.D. Anderson Cancer Center

(June 2018 product HPC, Cord Blood)

Ironically, while the FDA is now regulating unrelated cord blood transplants as a drug, unrelated bone marrow transplants are continuing to operate outside this regulation. Obviously this is creating a disproportionate burden on the providers of cord blood transplants. Moreover, public cord blood banks can only release transplants for the specific indications that have already received FDA approval; any transplants for novel indications can only be performed under a clinical trial (ie: after the trial sponsor files an IND application).

The new FDA regulations increase the financial burdens on public cord blood banks, limit their practices, and necessitate a re-examination of their business models. The public cord blood banks have a larger cost burden than providers of bone marrow transplants and have to limit the use of their samples. Likewise the family cord blood banks must be wary of what the FDA determines to be minimal manipulation and homologous use, and unless they send patients to participate in clinical trials, they are limited to the use of cord blood for immune system reconstitution as well.

Patient advocates have argued that the long FDA process of drug approval hinders access to life-saving therapies. A court case, Abigail Alliance v. von Eschenbach, was filed in 2006 in which the Abigail Alliance argued that the FDA should be forced to license drugs for use by terminally ill patients with "desperate diagnoses" after they have completed Phase I safety testing. The case won an initial court hearing in May 2006, but the FDA appealed it and that decision was reversed after the case was reheard in March 2007. The US Supreme Court declined to hear the case, and that decision has effectively denied terminal patients the right to try unapproved medications.