Jste zde

What is umbilical cord milking and when is it done?

Umbilical cord “milking”, also referred to as “stripping” the umbilical cord, is a controversial procedure that is sometimes employed after a baby is born. The technique involves grasping the side of the umbilical cord that is attached to the baby, holding it between the forefinger and thumb, pressing gently, and pushing blood from the umbilical cord into the baby. The purpose of milking the cord is to increase the transfusion of blood from the cord to the baby in a short amount of time. Cord milking can be an alternative to delayed cord clamping in situations where delayed clamping is not feasible or is not yielding blood transfer1-10.

An example of a scenario where a healthcare provider might milk the cord is the delivery of a premature baby. Many times, preterm babies need immediate medical intervention and delayed cord clamping is not possible. In these situations, obstetricians who need to immediately clamp the umbilical cord can milk the cord first to facilitate cord blood transfer to the baby before handing the baby off for neonatal care.

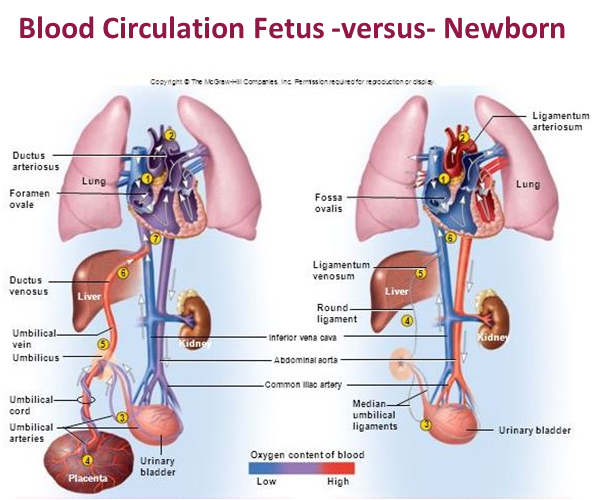

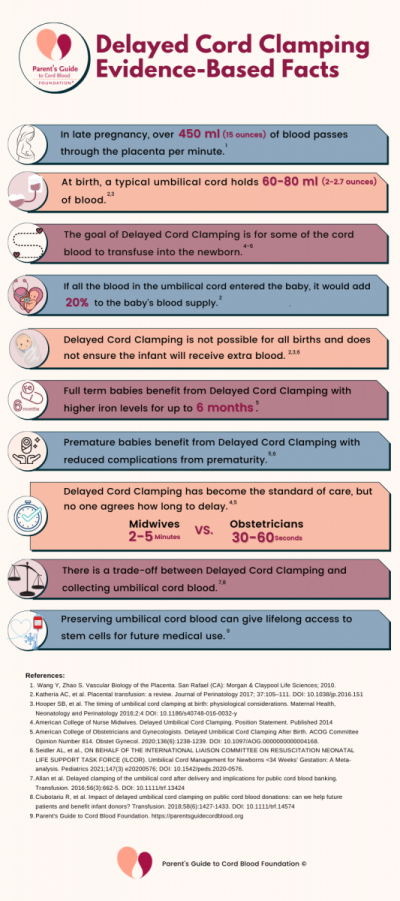

Delayed cord clamping is the practice of simply waiting after birth before clamping the umbilical cord1-4. The goal behind delayed cord clamping is to wait for some of the blood in the umbilical cord to enter the baby. Under the right circumstances, it is possible to “wait for white”, where the umbilical cord turns white because most of the blood that was in the cord has drained into the baby. However, delaying cord clamping does not guarantee that blood transfer from the cord to the baby will occur. The amount of blood transferred from the cord to the baby depends on many biologic factors, such as whether the baby was born by C-section, when the baby starts breathing, where the baby is held relative to the mother’s body, etc11-13.

Social media is full of claims that delayed cord clamping at the time of birth will produce healthier children, but the evidence from rigorous medical studies is more nuanced. Delayed cord clamping has been the topic of dozens of randomized controlled trials published in medical journals. For full term babies, delayed cord clamping has an immediate benefit of increasing the baby’s iron levels, and this benefit lasts until age 6 months1-4. It has never been proven conclusively that delayed cord clamping has any long-term health benefits for full term babies1,4. However, delayed cord clamping does have proven medical benefits for premature babies, where it reduces the incidence of several medical complications of prematurity1,4.

Delayed cord clamping has become the standard practice for infants that are born without complications, such as full-term babies that had vaginal deliveries. There is no consensus among medical societies on how long the time delay should be:

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends 30-60 seconds

- American College of Nurse Midwives (ACNM) recommends 2-5 minutes

- World Health Organization (WHO) recommends 1-3 minutes

Almost everyone agrees that umbilical cord blood is valuable, but there is a great deal of debate over how to best access that value for the baby, for the baby’s family, and for public health. A practice on one end of the spectrum is to clamp the cord immediately after birth and collect as much cord blood as possible for preservation in a cord blood bank. At the other end of the spectrum is to delay clamping for several minutes, in which case it probably will not be possible to collect any cord blood, either because it has drained from the cord or because it has clotted in the cord. A happy medium between these extremes would be to delay for 30-60 seconds and then collect cord blood, which is consistent with advice from US obstetricians1. In the case of cord blood donations for transplant patients, it is preferable to keep the delay short14,15. There is no clear data yet on how much cord blood transfer to the baby is sufficient to give the baby health benefits.

Almost everyone agrees that umbilical cord blood is valuable, but there is a great deal of debate over how to best access that value for the baby, for the baby’s family, and for public health. A practice on one end of the spectrum is to clamp the cord immediately after birth and collect as much cord blood as possible for preservation in a cord blood bank. At the other end of the spectrum is to delay clamping for several minutes, in which case it probably will not be possible to collect any cord blood, either because it has drained from the cord or because it has clotted in the cord. A happy medium between these extremes would be to delay for 30-60 seconds and then collect cord blood, which is consistent with advice from US obstetricians1. In the case of cord blood donations for transplant patients, it is preferable to keep the delay short14,15. There is no clear data yet on how much cord blood transfer to the baby is sufficient to give the baby health benefits.

Although cord milking is a well-known practice among labor and delivery caregivers, it is controversial because for premature babies it carries risks. The primary concern is that forcing blood into the baby’s abdomen too quickly will raise the baby’s blood pressure and could cause damage to small blood vessels in the brain. This is called intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH). Premature babies are already at risk for IVH, and studies have shown that when they receive some of their cord blood they are less likely to have IVH1. So here is the cord blood paradox for preterm babies: They would benefit from cord blood to prevent IVH, but if that cord blood is delivered too quickly it can trigger IVH.

Cord milking has not been as thoroughly studied as delayed cord clamping. There have been about ten randomized controlled clinical trials (RCT) that tested the impact of cord milking on large groups of babies. There have also been several “meta-analyses” of cord milking, in which researchers combined the data from multiple studies of various sizes to get a statistical overview5-10.

Cord milking has demonstrated measurable benefits for premature babies in studies against immediate cord clamping8. These include increases in blood pressure, hemoglobin, urine output, cerebral oxygenation, decreased risk of IVH, less chronic lung disease (measured by oxygen requirement), less necrotizing enterocolitis, and reduced need for transfusions. Very few trials have compared cord milking to delayed cord clamping9,10.

One study of cord milking for very premature babies raised alarms about the safety of the procedure9. A group at Sharp Mary Birch Hospital for Women & Newborns in San Diego launched a clinical trial of cord milking versus delayed cord clamping which planned to recruit 1500 infants that were born at less than 32 weeks gestation. This trial was halted after 474 infants had enrolled, due to higher rates of severe intraventricular hemorrhage in the cord milking group. Over all the children, the incidence of severe IVH was 8% in the cord milking group versus 3% in the delayed cord clamping group. Among the most premature babies, born at 23-27 weeks gestation, the rate of severe IVH was 22% in the cord milking group versus just 6% in the delayed cord clamping group. Since that study, some obstetricians have argued against milking the cord for very premature babies10.

There is still much that is unknown about cord milking, and most importantly we don’t know if it can be done safely for very premature babies. There is no consensus on whether cord milking should be performed before or after the umbilical cord is clamped. There is enormous variability in exactly how different groups “milk” the cord. The parameters of variability include how far down the cord to start (this is usually 20cm), how many times to push the blood towards the infant (usually 3-4), and how fast to push. It is possible that refining the technique of cord milking would lead to outcomes that are not only safe, but yield benefits for babies.

There is still an unmet medical need for an intervention that gives some umbilical cord blood to infants that are born prematurely, especially if those infants need resuscitation and it is not feasible to wait for delayed cord clamping8.

In March 2021, a review of umbilical cord management for babies born at less than 34 weeks gestation was published by the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation, Neonatal Life Support Task Force (also known as ILCOR)4. They reviewed 42 randomized controlled trials covering 5772 infants. They concluded that the current evidence for cord blood transfusion strategies is weak and more research is needed:

“Delayed cord clamping appears to be associated with some benefit for infants born <34 weeks. Cord milking needs further evidence to determine potential benefits or harms. The ideal cord management strategy for preterm infants is still unknown, but early clamping may be harmful.” – ILCOR 2021

Expectant parents should talk to their healthcare provider about the latest medical studies on delayed cord clamping and cord milking. It is best to do your research in advance and have a plan for how you would prefer your baby's birth to be managed, but always be mindful that if a medical need arises your team may have to switch to a fallback plan. Click here to download a Birth Plan Checklist from Parent’s Guide to Cord Blood Foundation.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping After Birth. ACOG Committee Opinion Number 814. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Dec;136(6):1238-1239. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004168

- American College of Nurse Midwives. Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping. Position Statement. Published 2014

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Delayed umbilical cord clamping for improved maternal and infant health and nutrition outcomes. WHO Guidelines Published 2014

- Seidler AL, et al., ON BEHALF OF THE INTERNATIONAL LIAISON COMMITTEE ON RESUSCITATION NEONATAL LIFE SUPPORT TASK FORCE (ILCOR). Umbilical Cord Management for Newborns <34 Weeks' Gestation: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2021 Mar;147(3) e20200576; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2020-0576

- Al-Wassia H, Shah PS. Efficacy and safety of umbilical cord milking at birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 2015 Jan;169(1):18-25. DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1906

- Katheria AC, Truong G, Cousins L, Oshiro B, Finer NN. Umbilical Cord Milking Versus Delayed Cord Clamping in Preterm Infants. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):61-69. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2015-0368

- Rabe H, Sawyer A, Amess P, Ayers S; Brighton Perinatal Study Group. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 2 and 3.5 Years for Very Preterm Babies Enrolled in a Randomized Trial of Milking the Umbilical Cord versus Delayed Cord Clamping. Neonatology. 2016;109(2):113-9. DOI: 10.1159/000441891

- Katheria AC. Umbilical Cord Milking: A Review. Frontiers Pediatrics 2018;6:335. DOI: 10.3389/fped.2018.00335

- Katheria AC, Reister F, Essers J, et al. Association of Umbilical Cord Milking vs Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping With Death or Severe Intraventricular Hemorrhage Among Preterm Infants. JAMA. 2019;322(19):1877–1886. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.16004

- Balasubramanian H, Ananthan A, Jain V, et al. Umbilical cord milking in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2020;105:572-580. DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-318627

- Farrar D, Airey, R, Law GR, et al. Measuring placental transfusion for term births: weighing babies with cord intact. BJOG 2011;118:70–75. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02781.x

- Hooper SB, Binder-Heschl C, Polglase GR, et al. The timing of umbilical cord clamping at birth: physiological considerations. Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology 2016;2:4 DOI: 10.1186/s40748-016-0032-y

- Katheria AC, Lakshminrusimha S, Rabe H, McAdams R, Mercer JS. Placental transfusion: a review. Journal of Perinatology 2017;37:105–111. DOI: 10.1038/jp.2016.151

- Allan DS, Scrivens N, Lawless T, et al. Delayed clamping of the umbilical cord after delivery and implications for public cord blood banking. Transfusion. 2016;56(3):662-5. DOI: 10.1111/trf.13424

- Ciubotariu R, Scaradavou A, Ciubotariu I, et al. Impact of delayed umbilical cord clamping on public cord blood donations: can we help future patients and benefit infant donors? Transfusion. 2018;58(6):1427-1433. DOI: 10.1111/trf.14574

Michelle McDougle, MS, CGC, earned her Master of Science in Genetic Counseling degree from UT Health Science Center in Houston, TX. Michelle joined CBR in 2017 and utilizes her training as a genetic counselor and clinical experience in prenatal and cancer genetics to lead CBR’s Clinical Science Liaison team in educating healthcare providers and families about the amazing potential of newborn stem cells. Frances Verter, PhD, is the founder of Parent’s Guide to Cord Blood and contributed to this article.

Michelle McDougle, MS, CGC, earned her Master of Science in Genetic Counseling degree from UT Health Science Center in Houston, TX. Michelle joined CBR in 2017 and utilizes her training as a genetic counselor and clinical experience in prenatal and cancer genetics to lead CBR’s Clinical Science Liaison team in educating healthcare providers and families about the amazing potential of newborn stem cells. Frances Verter, PhD, is the founder of Parent’s Guide to Cord Blood and contributed to this article.