当前位置

Regulatory T-cells from cord blood as ALS Therapy

Overview

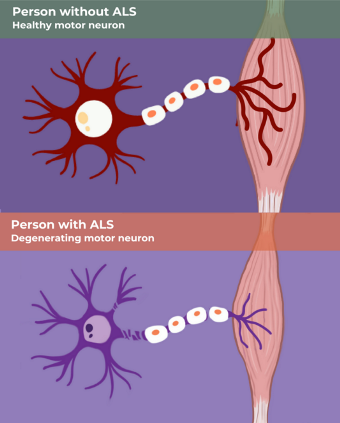

The neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is devastating because it is a progressive disease in which the motor neurons gradually deteriorate until the patient has no muscle control1,2. There is no cure for ALS, and there is not even a disease modifying therapy which can delay the progression. In the US, about 5,000 people are diagnosed with ALS each year, and their average life expectancy is only two to five years after diagnosis. Military veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with ALS, and this disparity has not been explained.

The neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is devastating because it is a progressive disease in which the motor neurons gradually deteriorate until the patient has no muscle control1,2. There is no cure for ALS, and there is not even a disease modifying therapy which can delay the progression. In the US, about 5,000 people are diagnosed with ALS each year, and their average life expectancy is only two to five years after diagnosis. Military veterans are more likely to be diagnosed with ALS, and this disparity has not been explained.

The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) recently published a study in which infusions of Regulatory T-cells (Tregs) derived from cord blood were able to slow the functional decline of ALS patients3. The accompanying commentary acknowledges that this approach “warrants careful consideration and cautious optimism”4.

The NJEM publication comes from phase 1 of clinical trial NCT05695521. In this safety study, a half dozen ALS patients received a fixed dose (100 million cells) of Tregs that was delivered by infusion weekly for four weeks (4 doses), and then monthly until the six-month mark (5 doses). The Tregs were supplied by Cellenkos, a biotech company in Houston, Texas, that manufactures Tregs from umbilical cord blood. The second portion of the study is currently enrolling 60 ALS patients into a randomized controlled clinical trial to determine if Tregs are a cell therapy that can extend and improve the lives of ALS patients.

What are Tregs and how do they work?

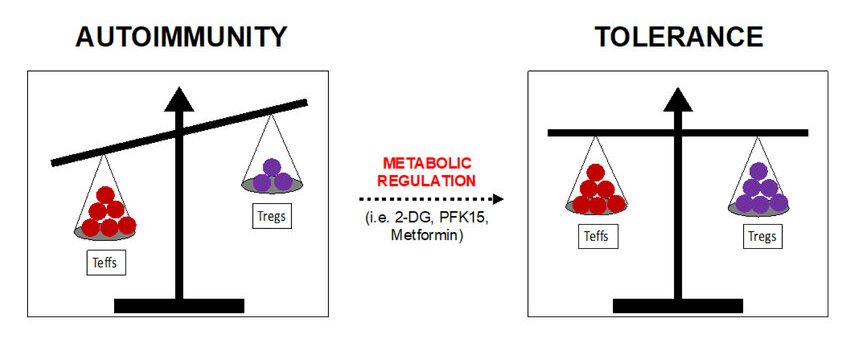

Regulatory T-cells are a subset of white blood cells that are responsible for regulating the immune response5-7. Tregs tell the body how to respond to foreign invaders called antigens, and they also prevent the body from over-responding in the form of auto-immune diseases. Each Treg cell only monitors response to a specific antigen, making it necessary for the immune system to create a wide variety of Tregs that are both natural as well as adaptive or induced. In addition to preventing auto-immune diseases, Tregs are important for controlling inflammation and fighting cancer cells8.

Because of their crucial role in regulating immune tolerance, researchers are testing Tregs as therapy for various auto-immune disorders. In addition to ALS, conditions that have been treated with Tregs in human clinical trials include graft versus host disease, post-transplant kidney rejection, lupus, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes, and others9-12.

Why treat ALS with T-regs?

Neuroinflammation is a hallmark of ALS. Hence, researchers have tested cell therapies that can disrupt the ALS inflammation process. There have been numerous studies of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) as therapy for ALS, based upon the well-known immunomodulatory ability of MSC to dampen inflammation13. In a mouse model of ALS, multiple studies have shown that MSC are neuroprotective, effectively delaying the onset of ALS and extending survival14. However, human clinical trials treating ALS with MSC have not conclusively demonstrated efficacy15. A fundamental problem is that, unlike in engineered mice, in humans ALS is a very variable disease. Most of the published trials of MSC for ALS have been early phase, with no control group to use as a baseline for measuring efficacy. Yet another issue is that the MSC must be administered in a way that enables therapeutic numbers of cells to migrate to the spinal cord of ALS patients. Currently researchers are waiting for the publication of results from later phase clinical trials of MSC for ALS15. This review of the MSC research for ALS may seem like a detour in this article about Tregs, but explaining the challenges encountered with MSC helps to explain why there is interest in cell therapy with Tregs14,15.

Tregs are very promising as a treatment for ALS because researchers have discovered that the Tregs in ALS patients are dysfunctional16,17. Moreover, it was found that in ALS patients the ability of their Tregs to suppress T lymphocytes correlated with the severity of their disease. Those ALS patients with worse clinical symptoms or with more rapidly progressing ALS were found to have greater Tregs dysfunction. In mouse models of ALS, infusions of Tregs significantly prolonged survival and preserved the size of motor neurons15,16. The treated mice were better able to make their own (endogenous) Tregs after the therapy. Based on this previous body of research, it is hypothesized that multiple infusions of Tregs could help the immune cells of ALS patients to quell neurotoxic inflammation16,17.

A final caution, from a neurologist who specializes in ALS, is that the “heterogeneity of ALS strongly suggests that no single intervention will address all forms of the disease”4.

Manufacturing Tregs for clinical use

Tregs are difficult to identify and characterize. In fact, there is more than one definition of Tregs in the medical literature8. After a 2014 workshop convened the world experts on this topic, it was decided that the minimum required cell surface markers to identify Tregs are CD3+, CD4+, CD25+, CD127-, and FOXP3+8. Based on this definition, Tregs account for about 10% of the CD4+ T-cells in circulating blood18.

Another level of complexity is that there is more than one type of Tregs. The two main types are naturally occurring Tregs and induced Tregs. The naturally occurring Tregs are produced in the thymus gland. The induced Tregs arise when T-cells encounter antigens under the right circumstances18. Induced Tregs can be purposely created in the laboratory, while natural Tregs can be ex vivo expanded18,19. Thus, it is possible to achieve high enough cell counts for clinical applications with either type of Tregs. But even this description is simplistic, as more research has uncovered more sub-groups of Tregs in older people20. This is an evolving field of research. “Furthermore, most of the studies on human Treg are based on circulating cells in the blood, which may not represent the real landscape in a given tissue”20.

Several companies have developed commercial kits for isolating Tregs21,22. Their procedures usually rely on cell separation with magnetic beads that attach to specific cell surface markers. Thus, when a magnetic field pulls the beads out of the cell mixture, you can select for or against cells with specific markers. However, some scientists argue that flourescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) yields a Treg product of higher purity23.

Umbilical cord blood is the richest source for natural Tregs, because the concentration of Tregs in human blood decreases with age20. Cord blood is also a superior source of “naieve” natural Tregs that have minimal exposure to disease antigens. Studies have shown that when Tregs from cord blood are expanded in culture, they are better than adult Tregs at maintaining a homogenous phenotype and maintaining their ability to suppress responder T-cells11,19,23. When Tregs are isolated from adult blood there is a risk of contamination with cells that will promote inflammation, but there is much less risk of this when cord blood is used as the source material23.

In summary, there are many variables that go into manufacturing a therapeutic Tregs product. It is a good bet that no two biotech companies are producing Tregs products that are even remotely similar.

The variables in Tregs clinical products:

- Source of the Tregs - cord blood or adult blood?

- Cell surface markers used to identify Tregs?

- Purity of the Tregs isolation from T-cells?

- Any selection for natural Tregs versus induced Tregs?

- Tregs from multiple donors, or expanded in culture, or both?

- Tregs are polyclonal or select for antigen-specific?

- Are the Tregs genetically engineered, such as CAR-Tregs?

Commercialization of T-regs

The study published in NEJM that treated ALS patients with Tregs used the product CK0803 that is developed by Cellenkos, a biotech company that was spun off from MD Anderson Cancer Center in 2016 to develop a proprietary platform that manufactures Tregs from umbilical cord blood. Their manufacturing platform is called CRANE®, which stands for Cord Blood T-Regulatory Cells; Activated and Enriched24. Cellenkos has four Tregs products, where each product is “activated” to target a different disease. The product CK0803 for ALS contains Tregs that “are modified to overexpress CD11a and CXCR3, improving their ability to migrate to inflamed brain regions, specifically, inflamed microglia”25. The Cellenkos “enrichment” phase expands enough Tregs from a single cord blood unit to create a treatment dose (100 million cells), which is then cryopreserved for off-the-shelf use24. Their treatment protocol does not use HLA matching between the patient and the donor of the dose.

The study published in NEJM that treated ALS patients with Tregs used the product CK0803 that is developed by Cellenkos, a biotech company that was spun off from MD Anderson Cancer Center in 2016 to develop a proprietary platform that manufactures Tregs from umbilical cord blood. Their manufacturing platform is called CRANE®, which stands for Cord Blood T-Regulatory Cells; Activated and Enriched24. Cellenkos has four Tregs products, where each product is “activated” to target a different disease. The product CK0803 for ALS contains Tregs that “are modified to overexpress CD11a and CXCR3, improving their ability to migrate to inflamed brain regions, specifically, inflamed microglia”25. The Cellenkos “enrichment” phase expands enough Tregs from a single cord blood unit to create a treatment dose (100 million cells), which is then cryopreserved for off-the-shelf use24. Their treatment protocol does not use HLA matching between the patient and the donor of the dose.

Industry analysts count about 50 groups developing Treg products for commercialization, including publicly traded companies, privately held companies, and university laboratories26. This is a very competitive space, made more so by the uncertainty of biotech funding for early-stage clinical trials in 202527. For example, Cellenkos is not the only company in Houston that is developing a Tregs product to treat ALS; their hometown competitor Coya Therapeutics was also founded in 201628. For example, Abata Therapeutics received FDA fast track for their Tregs product in August 2024, but in August 2025 they suddenly shut down29,30.

Cellenkos has recently signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre (KFSHRC) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia31. The agreement with Cellenkos is one of several collaborations in medical innovation that were signed by KFSHRC during the Saudi-U.S. Investment Forum 202532. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia wants to adopt cutting-edge medical technology that will reduce the need for their patients to seek treatment abroad, and will reinforce their position as a regional hub for specialized healthcare. Under the terms of the MOU, KFSHRC will invest in clinical trials to treat graft versus host disease and aplastic anemia, using the Cellenkos Tregs product CK080131,33. In exchange, Cellenkos will provide crucial assistance to KFSHRC in establishing local infrastructure for cell and gene therapy manufacturing, training, and education31.

Conclusions

Tregs show great promise as a cell therapy for ALS as well as other conditions that are neuro-degenerative or auto-immune. The inherent complexity of Tregs practically guarantees that multiple companies will commercialize them with different product designs. Nonetheless, Tregs sourced from cord blood will probably play a significant role in this field, because cord blood is the ideal source of natural Tregs and readily lends itself to manufacturing off-the-shelf products.

References

- Wexler M. ALS Overview. ALS News Today. Published 2023-03-20

- ALS Association. Who Gets ALS?

- Shneider NA, Nesta AV, Rifai OM, ... Parmar S. Clinical Safety and Preliminary Efficacy of Regulatory T Cells for ALS. NEJM 2025; 4(5).

- Abati E. Regulatory T Cell-Based Therapies — A New Piece of the ALS Therapeutic Puzzle? NEJM 2025; 4(5).

- Cleveland Clinic. Regulatory T cells. Last reviewed 2022-07-13

- Vignali D, Collison L. & Workman C. How regulatory T cells work. Nature Rev Immunology. 2008; 8:523–532.

- Cells at Work! Regulatory T Cell. Fandom.

- Santegoets SJAM, Dijkgraaf EM, Battaglia A, ... van der Burg SH. Monitoring regulatory T cells in clinical samples: consensus on an essential marker set and gating strategy for regulatory T cell analysis by flow cytometry. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy. 2015; 64(10):1271–1286.

- Li W, Deng C, Yang H, Wang G. The Regulatory T Cell in Active Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers Immunology. 2019; 10:159.

- Schreeb KH, Atkinson GF, Chapman C, ... Harden PN. STEADFAST Study Update: A Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial of Regulatory T Cells Expressing a Chimeric Antigen Receptor Directed Towards HLA-A2 in Renal Transplantation. Am J Transplantation. 2025; 25(8 Sup1):S265.

- Bi Y, Kong R, Peng Y, ... Zhou Z. Multiply restimulated human cord blood-derived Tregs maintain stabilized phenotype and suppressive function and predict their therapeutic effects on autoimmune diabetes. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2024; 16:71.

- Wardell CM, Boardman DA, Levings MK. Harnessing the biology of regulatory T cells to treat disease. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2025; 24:93–111.

- Pittenger MF, Discher DE, Péault BM, Phinney DG, Hare JM, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: cell biology to clinical progress. Nature Regenerative Medicine. 2019; 4:22.

- Ciervo Y, Ning K, Jun X, Shaw PJ, Mead RJ. Advances, challenges and future directions for stem cell therapy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2017; 12:85.

- Abati E, Bresolin N, Comi G, Corti S. Advances, challenges, and perspectives in translational cell therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Molecular Neurobiology. 2019; 56:6703-6715.

- Sheean RK, McKay FC, Cretney E, ... Turner BJ. Association of Regulatory T-Cell Expansion With Progression of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. A Study of Humans and a Transgenic Mouse Model. JAMA Neurology. 2018; 75(6):681-689.

- Beers DR, Zhao W, Wang J, ... Appel SH. ALS patients’ regulatory T lymphocytes are dysfunctional, and correlate with disease progression rate and severity. JCI Insight. 2017; 2(5):e89530.

- Schmitt EG, Williams CB. Generation and Function of Induced Regulatory T Cells. Frontiers Immunology. 2013; 4:152.

- Hippen KL, Merkel SC, Schirm DK, ... Blazar BR. Massive ex Vivo Expansion of Human Natural Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) with Minimal Loss of in Vivo Functional Activity. Science Translational Medicine. 2011; 3(83):83ra41.

- Rocamora-Reverte L, Melzer FL, Würzner R, Weinberger B. The Complex Role of Regulatory T Cells in Immunity and Aging. Frontiers Immunology. 2021; 11:616949.

- Miltenyi. Regulatory T cells.

- StemCell Technologies. EasySep™ Human CD4+CD127lowCD25+ Regulatory T Cell Isolation Kit.

- Motwani K, Peters LD, Vliegen WH, ... Brusko TM. Human Regulatory T Cells From Umbilical Cord Blood Display Increased Repertoire Diversity and Lineage Stability Relative to Adult Peripheral Blood. Frontiers Immunology. 2020; 11:

- Cellenkos. Our science.

- Cellenkos. Cellenkos' Off-the-Shelf Treg Cell Therapy Shows Clinical Safety and Preliminary Efficacy in ALS. PR Newswire. Published 2025-04-22

- VentureRadar. Treg Companies. Accessed 2025-08-28

- Mendoza AB. Navigating the 2025 Biotech Funding Squeeze: A Blueprint for Early-Stage Success. Blueprint for Breakthroughs. Published 2025-02-11

- Coya Therapeutics Accessed 2025-08-28

- Abata Therapeutics. Abata Therapeutics Receives FDA Fast Track Designation for ABA-101 for the Treatment of Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Abata News. Published 2024-08-22

- Masson G, Incorvaia D. Fierce Biotech Layoff Tracker 2025. Fierce Biotech. Accessed 2025-08-28

- Cellenkos. Cellenkos Inc. and King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre, Sign Strategic MOU to Advance T Regulatory Cell Therapies for Unmet Diseases. PR Newswire. Published 2025-05-22

- King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre. KFSHRC Signs Five International Agreements to Advance Medical Innovation at Saudi-U.S. Investment Forum. News. Published 2025-05-14

- Kadia TM, Ma H, Zeng K, ... Verstovsek S. Phase I Clinical Trial of CK0801 (cord blood regulatory T cells) in Patients with Bone Marrow Failure Syndrome (BMF) Including Aplastic Anemia, Myelodysplasia and Myelofibrosis. Blood. 2019; 134(S1):1221.