Jste zde

Cord Blood Proven Effective for Cerebral Palsy

What is new?

A paper has just been published, in the prestigious peer-reviewed journal Pediatrics, which statistically demonstrates that cord blood cell therapy is an effective treatment for improving the gross motor skills of children with cerebral palsy (CP)1. This paper is the outcome of an international collaboration which performed an Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis (IPDMA) on results from over 400 children with CP from 11 studies. We previously reported on a poster version of this research which was presented in Sept. 2023, but now the full paper is published1,2.

What are the results?

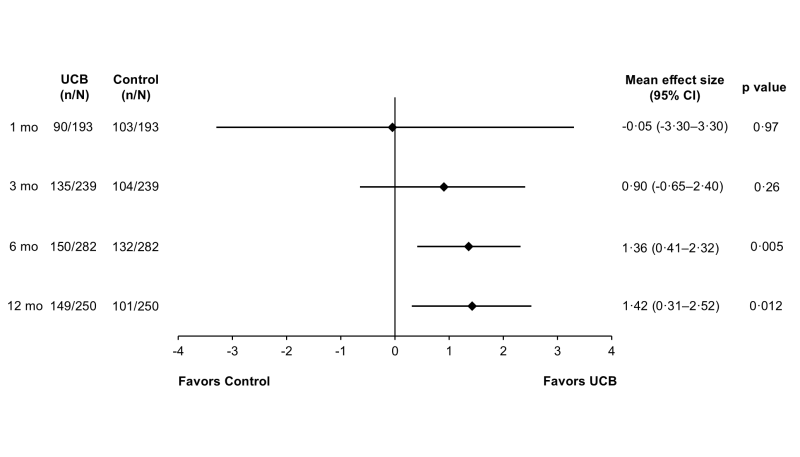

The high-level picture is that cord blood treatment, in combination with rehabilitation, improves gross motor skills in children with CP significantly more than rehabilitation alone. It must be emphasized that, relative to the field of physical therapy for children with CP, the size of the clinical effect from cord blood is considered to be “a large treatment effect”3. The IPDMA study also revealed that the improvements in motor scores peak between 6 and 12 months after the cord blood cell therapy, and that there is a dose-response trend where higher cell doses yield bigger improvements in motor skills. The analysis identified best responders as children with CP that are under age five years and who have some ability to walk, either independently or with assistance, before the therapy.

Figure 1 from Finch-Edmondson M, et al. Pediatrics. 2025; 155(5):e2024068999.

The key numbers and trends in the results are as follows:

- At 6 months after cord blood cell therapy, the cord blood-treated participants were doing better than the control group by an average improvement in their GMFM-66 motor skill score of 1.36 (95% CI: 0.41, 2.32; p=0.005).

- By 12 months after cord blood cell therapy, the average improvement in the GMFM-66 scores between cord blood-treated participants and controls was 1.42 (95% CI: 0.31, 2.52; p=0.012).

- The peak in response at 6 to 12 months after treatment is consistent with the hypothesized mechanism of action: that the cord blood works through a paracrine effect that reduces neuro-inflammation, stimulates endogenous tissue repair, and thus leads to increased brain connectivity.

- There was a trend of better response with higher Total Nucleated Cell (TNC) dose in participants receiving cord blood infusions, provided the cell dose was above 50 million TNC/kg (p=0.047 at 12 months). These doses were measured prior to cryopreservation.

- There was a trend of better response in younger children with CP.

- There was a trend of better response among children with milder CP, defined as Gross Motor Function Classification System levels 1-3 on a scale of 5. This trend held up even after corrections were made for baseline age and prematurity at birth.

Additional details about the cord blood treatments:

- The study collected data on a total of 498 treatments over 447 participants. The IPDMA presented in the Pediatrics publication excluded participants that received erythropoietin, relying solely on data from 170 cord blood-treated participants and 171 controls1. However, the earlier poster publication demonstrated similar results with the inclusion of participants that received cord blood plus erythropoietin2.

- Most of the children had spastic CP (90%) and efforts were made to exclude genetic disorders that cause symptoms like CP.

- The mean age of the treated children at baseline was 57 months (range 8 to 227).

- The cord blood cells were delivered by systemic infusion in 10 of the 11 studies, and the remaining study was intrathecal.

- The median pre-thaw dose of the infusions was 56.1 million TNC/kg (range 9.7 to 210.3).

- In 84% of the treatments, the cord blood did not come from the patient (autologous), but from a donor (related or unrelated allogeneic).

What this study means for parents of children with CP

Pediatrics published a Commentary to the IPDMA paper that was authored by two experts in the field of physical therapy rehabilitation for children with CP3. They stressed that knowledge of which children are best responders to cord blood therapy is “critical to shared decision-making with families.” When a family has a child with CP, of course their primary concern is not the group differences, but whether an intervention is likely to benefit their child. We have learned from the IPDMA analysis that, after 6 to 12 months, 68% of the children who received cord blood therapy had GMFM-66 scores that were higher than the entire control group. But we have also learned that this dramatic improvement in gross motor skills is most likely to occur for younger children and for children who were higher functioning at the start of treatment.

It is now established that CP can be accurately diagnosed as early as 6 months of age, and the GMFM-66 scale can be used for children as young as 5 months1. Early diagnosis opens the door for more families to take advantage of cord blood therapy during the period of optimal brain neuroplasticity. Moreover, earlier treatment can make it easier to achieve high doses of TNC/kg because the child is still small, and it may allow the option of multiple rounds of therapy before the child ages out of the window of therapeutic efficacy4.

What this study means for public health policy

At this time, cord blood therapy for CP has not achieved market approval in any country. There is a long-standing need for prospective phase 3 trials of this treatment, which will be cumbersome and expensive but is still the typical pathway to market approval5. In the meantime, the mounting evidence for efficacy of cord blood therapy as a treatment for CP calls for adjustments to public health policy. These include education around the topic, organization of late phase trials, and the establishment of regulatory pathways to access the treatment.

Education is necessary because CP is not a well-known diagnosis among parents of young children, even though it is the most common motor disability of childhood1,6. The CDC estimates that 1 in 345 eight year olds in the US have this condition6. The incidence of CP rises dramatically with premature birth, reaching 15% among babies born between 24-27 weeks gestation1,7. The lifetime cost of caring for a child with CP is over a million dollars, and most of that expense is the indirect cost of lost productivity6,8. Both obstetricians and expectant parents should be educated about the fact that cord blood therapy is an option if a baby develops CP. This knowledge might motivate more parents to save their baby’s cord blood at birth.

There are a limited number of hospitals and clinics worldwide which presently offer cord blood therapy for CP under the umbrella of an authorized regulatory pathway. It is well established that the treatment is very simple and has a robust safety profile5,9. Given the heterogeneity that has plagued previous clinical trials of cell therapy for CP, it would benefit the patient community if research organizations could cooperate and share resources to hold multi-national trials.

The reservoir of cord blood units for these treatments already exists. Most of the children in the IPDMA study used cord blood from donors, and future treatments can draw on the existing worldwide network of public cord blood banks10. More research is needed to quantify a maximum advisable dose of TNC/kg for this therapy, and to learn whether it is reasonably safe to combine small cord blood units to achieve a higher therapeutic dose.

Finally, we must deal with the reality that access to cord blood therapy for CP is not available to all patients and their families. Many countries have compassionate use pathways that allow seriously ill patients to access experimental treatments which show promise but do not yet have market approval. The IPDMA study was coordinated by the Cerebral Palsy Alliance of Australia, and thanks to their efforts Australia has joined the ranks of countries which allow compassionate access to cord blood therapy for CP. However, many families continue to resort to medical tourism in order to obtain this therapy, and regulatory access remains one of the biggest challenges in this field.

References

- Finch-Edmondson M, Paton M, Webb A, Ashrafi M, Blatch-Williams R, Cox CJ, ... Novak I. Cord Blood Treatment for Children With Cerebral Palsy: Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics. 2025; 155(5):e2024068999.

- Finch-Edmondson M, on behalf of the study team. Meta-Analysis of Cord Blood for Cerebral Palsy. Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Foundation Newsletter Published 2023-11

- Rosenbaum P, Palisano R. Cord Blood Treatment for Children With Cerebral Palsy (Commentary). Pediatrics. 2025; 155(5):e2024070467

- McDonald C. Multiple Doses of Cord Blood are Better for Cerebral Palsy in Animal Model. Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Foundation Newsletter Published 2019-06

- Paton MCB, Finch-Edmondson M, Fahey MC, London J, Badawi N, Novak I. Fifteen years of human research using stem cells for cerebral palsy: A review of the research landscape. J. Paediatrics Child Health. 2021; 57(2):295-296.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Data and Statistics for Cerebral Palsy. Archives. Last reviewed 2022-05-02

- Stavsky M, Mor O, Mastrolia SA, Greenbaum S, Than G, Erez O. Cerebral Palsy—Trends in Epidemiology and Recent Development in Prenatal Mechanisms of Disease, Treatment, and Prevention. Frontiers Pediatrics 2017; 5:21.

- Honeycutt A, Dunlap L, Chen H, Gal H, Grosse S, Schendel D. Economic costs associated with mental retardation, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, and vision impairment--United States, 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2004; 53(3):57-9.

- Paton MCB, Wall DA, Elwood N, Chiang K-Y, Cowie G, Novak I, Finch-Edmondson M. Safety of allogeneic umbilical cord blood infusions for the treatment of neurological conditions: a systematic review of clinical studies. Cytotherapy. 2022; 24(1):2-9.

- Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Foundation. Public Cord Blood Banks in my Country. Accessed 2025-04-12